Thursday, May 11, 2006

if you like frank o'hara so much why don't you just go and live there?

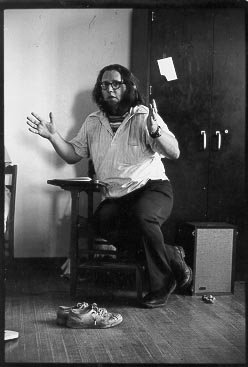

Kind and charming remarks from Jon and Neil in yesterday's comments set me thinking. I've been writing a short thing for my friend Jack who wanted a kind of 'How To Get Started' kit for reading poetry, and a bit of it seemed relevant. When Jon suggests that I might live more 'sharply' (good word) than he, I feel duty bound to point out that that 'sharpness', Neil's term is 'crystal clear focus', is a function of the poems, not of my life (sharp is not the word that would spring to your mind if you knew what I've been doing recently). I was trying to get across this very idea in my thing for Jack. I should really have used Ted Berrigan's fantastic poem 'American Express' as an example but it's too long and weirdly indented to type up, so I went for O'Hara again, but posted a picture of Ted to make up for it. I'm imposing a one month O'Hara moratorium starting today. Anyway, this is what I said to Jack:

Here’s a thing to think about. Douglas Oliver, a fantastic British poet who died a few years ago quite young, described some of the poetry of Ted Berrigan in this way: he said the poems were ‘a form of cognition’. What he means by that, I think, is that the poems are not a description of anything. They don’t contain knowledge like a cup contains tea, nor do they transmit anything. They are something: a type of knowledge. Something clicks in the poem. When you get a poem right it makes a type of knowledge exist that just couldn’t exist otherwise. The wonderful but dangerously influential American poet Frank O’Hara starts off lots of his poems by telling you the time and you have to think hard what that means. Does he mean that’s the time the events in the poem happened, or the time he’s writing the poem, or what? And when you read it what happens? Are you supposed to imagine it’s that time? It’s the very first thing, it’s at the front for a reason. (I was just going to quote the start of this but you might as well see the whole thing, eh?)

The Day Lady Died

It is 12:20 in New York a Friday

three days after Bastille day, yes

it is 1959 and I go get a shoeshine

because I will get off the 4:19 in Easthampton

at 7:15 and then go straight to dinner

and I don't know the people who will feed me

I walk up the muggy street beginning to sun

and have a hamburger and a malted and buy

an ugly NEW WORLD WRITING to see what the poets

in Ghana are doing these days

I go on to the bank

and Miss Stillwagon (first name Linda I once heard)

doesn't even look up my balance for once in her life

and in the GOLDEN GRIFFIN I get a little Verlaine

for Patsy with drawings by Bonnard although I do

think of Hesiod, trans. Richmond Lattimore or

Brendan Behan's new play or Le Balcon or Les Nègres

of Genet, but I don't, I stick with Verlaine

after practically going to sleep with quandariness

and for Mike I just stroll into the PARK LANE

Liquor Store and ask for a bottle of Strega and

then I go back where I came from to 6th Avenue

and the tobacconist in the Ziegfeld Theatre and

casually ask for a carton of Gauloises and a carton

of Picayunes, and a NEW YORK POST with her face on it

and I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of

leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT

while she whispered a song along the keyboard

to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing

So that’s a poem about Billie Holiday dying. Her nickname was Lady Day, geddit? And what does Frank say about it? Not much. It starts with him saying the time, then imagines a little way ahead, not worrying exactly, but conscious of not knowing ‘the people who will feed me’. A bad poet might try and make something of that, you know, the future’s uncertain, blah blah. He just leaves it there, then he’s bustling about town, hot and indecisive, absent mindedly thinking about things. He names places and people, books, brands of cigarette, then he sees a newspaper with the news of her death, and remembers seeing her perform. The ‘12.20’ acts as a kind of pivot for the poem to hang on, lean a little forward (timetabled, on tracks), lean back a little. In the middle of the poem, Frank is ‘practically going to sleep with quandariness’, and at the end, after arriving ‘back where I came from’ he’s stopped breathing, and Billie Holiday’s dead. All these things are put together in a way that is about memory, about death (sleeping, not breathing, I hear ‘John Doe’ in that ‘john door’…) , about time and the way it stops, swirls about, lurches and leans, and somehow partly by saying ‘It is 12:20 in New York a Friday’ at the start the creation of that piece of knowledge actually happens in the poem. The poem doesn’t try and explain a set of feelings, or draw parallels between things to try and make a point, it is a separate thing in itself. It’s in the world, of course, so it acknowledges the world, the names of its roads and restaurants, but it’s not a report: it’s a warm little ball of knowing, it is something clicking, and you can go back to it again and again and again and it’ll never wear out. Read it out loud, you’ll see what I mean. Now I’m not a religious man, I have no use for eternity, as far as I can see it’s just you and me kid, and this kind of knowing is not an epiphany, but it is, as our hairy elders would say, a trip. A trip back to here.

Comments:

<< Home

Three o'clock in the morning, that's a fine time to be writing this sort of thing. Tutorial, critique, how-to? It's got me thin king too.

I love that picture of Ted Berrigan, by the way.

Post a Comment

I love that picture of Ted Berrigan, by the way.

<< Home